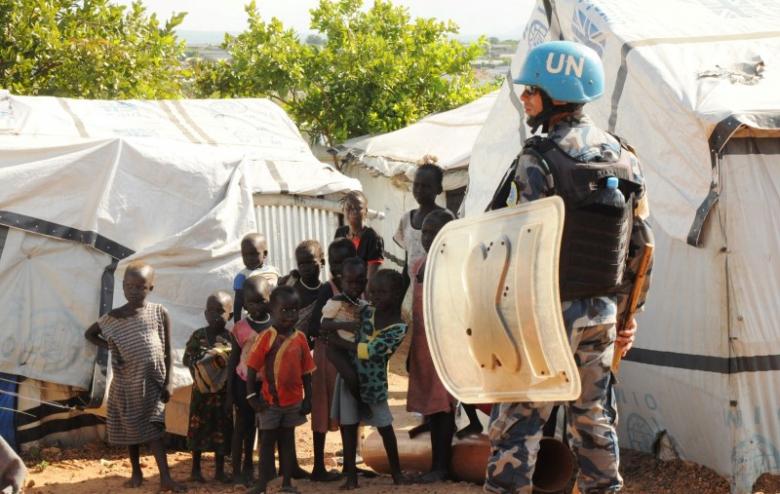

United Nations peacekeepers in South Sudan are moving more aggressively to protect civilians caught in the country’s four-year civil war, after years of criticism for failures that led to the sacking of the mission’s military chief last year.

This year, the U.N. Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) has rescued aid workers and U.N. staff during attacks, saved civilians from abduction by armed groups, and pushed past roadblocks to a massacre site.

“A lot has been done … to improve UNMISS’ ability to deliver on its protection of civilians mandate,” said Lauren Spink, a South Sudan specialist for the independent U.S.-based advocacy group Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC).

South Sudan was the world’s youngest country when it became independent from neighboring Sudan in 2011 following decades of conflict.

But the new nation dissolved into civil war less than two years later, after President Salva Kiir, an ethnic Dinka, fired his deputy, Riek Machar, a Nuer.

Since then tens of thousands have died, and 3.5 million of the country’s 12 million citizens have fled their homes, creating Africa’s largest refugee crisis since Rwanda’s 1994 genocide.

BASE PROTECTION

As the war spread, families flooded into U.N. bases seeking protection. More than 210,000 people now stay in six such bases, too fearful to go home.

Between December 2013 and July 2016, more than 100 civilians and four U.N. peacekeepers were killed in attacks on U.N. bases when peacekeepers didn’t shoot back, fled, or delayed responding, according to data from the U.N. and CIVIC.

But a chastened UNMISS has gradually taken a tougher stance, boosted by the January arrival of new chief David Shearer, a former New Zealand labor party leader.

“We are trying to make our peacekeeping more robust,” Shearer told Reuters. “Our peacekeepers are going to stand up to situations and challenge them.”

Several incidents demonstrate the change. In April, peacekeepers deployed to Aburoc, a village on the Nile. After the U.N. arrived, rebels withdrew, and a government offensive that had displaced 20,000 civilians paused. Aid workers then intervened to stop a cholera outbreak.

The same month, peacekeepers went to Torit in the southeast to protect an orphanage housing 250 children caught between the front lines.

Mongolian peacekeepers in northern Bentiu town have repeatedly rescued civilians from abduction by armed groups this year, including one incident where they fired their weapons. Reuters was unable to find records of such interventions for previous years.

“There is improvement,” said Peter Ruach, who lives in the camp outside the U.N. base in Juba. A year ago government troops raped dozens of women who ventured outside the fence to search for food.

“The Ethiopian battalion have cleared a buffer zone and they make sure that when women are going out for collection of firewood they are protected,” he said.

Since the buffer zone opened at the end of November, serious crimes like rape and murder reported near the camp had dropped from around 48 per month to between 1 and 5, the U.N. said.

STRAINED HISTORY

Chinese Peacekeepers in the United Nations Mission to South Sudan (UNMISS) ride in their armoured personnel carriers (APC) as they wait in the queue to enter their base in Juba, South Sudan August 1, 2017.

U.N. peacekeepers have been in South Sudan since before independence, but found themselves frequently criticized after war broke out by aid groups like Doctors Without Borders, who said they were not doing enough to protect civilians.

A year ago, peacekeepers at the U.N.’s main Juba base ignored desperate pleas for help when government troops attacked a hotel a mile away, killing one aid worker and gang-raping others.

In following days, government troops raped dozens of Nuer women outside the same base. Ten aid agencies released a joint statement accusing peacekeepers of failing to adequately patrol the area.

“The inability of UNMISS to protect civilians threatens to undermine any attempts at safety and security in the country and makes it impossible for humanitarian agencies to provide the help that is so urgently needed,” Frederick McCray, South Sudan Country Director at charity CARE, said at the time.

The U.N. eventually launched an investigation that led to the firing of UNMISS’ top general, Kenya’s Johnson Ondieki, in November. In response, Kenya pulled its troops from the peacekeeping mission.

PROBLEMS REMAIN

Despite more robust peacekeeping, the violence continues. The mission has 12,000 armed peacekeepers and a budget of over a billion dollars. But that’s not enough to patrol a nation the size of France with under 300 km (185 miles) of paved roads.

Peacekeepers were too stretched to deploy to Pagak, a rebel stronghold in the northeast, where a government offensive has displaced thousands and forced dozens of aid workers to evacuate since July, Shearer said.

U.N. patrols did not intervene in the northwestern town of Wau in April when a government-aligned Dinka militia went door-to-door, executing at least 16 people of other ethnicities.

Part of the problem is that the U.N. needs permission from South Sudan’s government for its presence. That can interfere with investigations or interventions aimed at government forces.

Last week, the government grounded U.N. flights after a dispute about the deployment of an additional 4,000 troops to beef up the peacekeeping mission. The government is reluctant to accept the new force.

“The U.N. cannot be totally independent in a country that is sovereign. They need to be working in cooperation with the government … They cannot run a parallel government,” said presidential spokesman Ateny Wek Ateny.

He denied that government forces had killed or abused civilians.

“Government … cannot do anything harmful to civilians that requires someone to come and protect them,” Ateny said.

Shearer has responded to some roadblocks with public pressure. He took to U.N. radio to demand access to the Torit orphanage, and has ordered peacekeepers to hold their ground when their patrols are blocked by troops.

“We’ve had several instances of platoons sleeping at checkpoints for up to three days until they were finally persistent enough to be allowed to go,” he said.

But for some, U.N. intervention came too late. The U.N. did not arrive in Aburoc until April, well after the government offensive began in January.

In the meantime, government forces killed civilians, bombing and shelling the area, and burning people alive in their homes, rights body Amnesty International said.

[Source: Reuters]

WhatsApp us

WhatsApp us